2014 looks like being the year of the hoax in Japan. Three whoppers have been exposed already, each extraordinary in its own way.

The most damaging to Japan’s interests were the confessions of Seiji Yoshida, a self-admitted procurer for the Imperial Japanese Army. Starting in 1982 the Asahi Shimbun, Japan’s leading progressive newspaper, ran a series of articles featuring Yoshida’s horrific tales of kidnapping hundreds of young Korean women and despatching them to brothels in occupied Asia.

The comfort women became an international cause célèbre, poisoning relations with South Korea and sparking hearings in the US Congress and calls for billions of dollars of reparations.

Yoshida provided no evidence beyond his own say-so and some details contradicted contemporary sources. Despite the discrepancies, the Asahi stuck by its man until this August, fourteen years after his death, when it finally admitted his testimony was fraudulent. Historians will continue to debate the super-sensitive issue of the comfort women, but the Asahi’s reportage has been discredited.

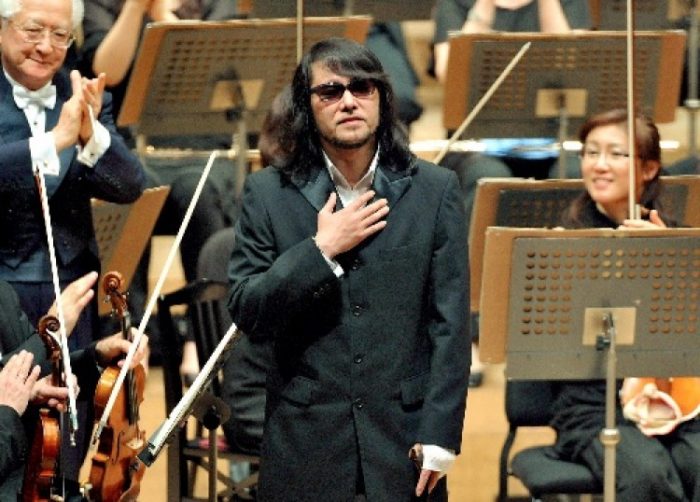

Much stranger was the case of the “Japanese Beethoven.” Mamoru Samuragochi was a successful classical composer who suffered from total hearing loss. His Symphony of Hope was performed in front of the G8 leaders in 2008 and the CD sold 180,000 units. His fame soared to new heights after the national broadcaster, NHK, made a documentary, Melody of the Soul – the Composer who Lost his Hearing, which showed him touring the tsunami-battered Tohoku coast and consoling survivors.

If the story seemed too good to be true, that’s because it was. Samuragochi was a total fraud. Not only was he not deaf, but he wasn’t even a composer! According to the little-known professor of music who he paid to create his oeuvre, he can’t read music and plays the piano like a beginner. When the ghost-writer went public, the deception collapsed.

Science is supposed to be more objective than the arts so the case of Haruko Obokata was doubly shocking. Young, female and highly photogenic, Obokata was a star researcher at the Riken Center for Developmental Biology. When she published ground-breaking work on regenerative cells, she was tipped as a future Nobel laureate. But her fall from grace came fast. Within weeks she was accused of falsifying data. Her university rescinded her PhD and tragedy followed with the suicide of her supervisor at Riken.

In all three cases, the stories fitted the pre-existing media agenda. As the conscience of the Japanese left, the Asahi tends to emphasize Japanese war guilt and the need to make amends with neighbouring countries. NHK is ever on the lookout for heart-warming stories of triumph against adversity, particularly after the disasters of March 2011. In the age of officially-sanctioned “womenomics,” the Japanese press yearned for a charismatic female role model like Obokata.

Foreign approval played a role too. Nature, the prestigious British journal, published Obokata’s dodgy research without a sceptical murmur. It was Time magazine that dubbed failed rock singer Samuragochi the Japanese Beethoven. Likewise Yoshida’s fibs were meat and drink to foreign journalists eager to emphasize the uniqueness of Japan’s wartime depredations.

There’s nothing specifically Japanese about what happened. The Obokata scandal parallels the even more sensational case of South Korea’s Hwang Woo-suk, whose fabricated “success” in cloning human stem cells caused Time to name him one of its “People Who Matter 2004.” And who can forget the fake sign language interpreter who briefly suckered the world’s media at Nelson Mandela’s funeral?

Hoaxes crop up in all eras and all corners of the earth, taking in the mighty and the humble, the sophisticated and the naïve. The medieval period is full of nonsensical rumours, forgeries and scams, many perpetrated in the name of religion, such as the proliferation of sacred foreskins. The fourteenth century Travels of Sir John Mandeville, a purported travel memoir, described tribes of people with eyes in their shoulders and sheep that grow on trees. If recent suspicions that Marco Polo never visited China are correct, then his 800 year old hoax would be one of the longest-running ever.

Today we live in the era of the internet, where information supposedly “wants to be free.” Pulling the wool over people’s eyes should be more difficult. That does not appear to be the case. Instead the internet itself has become a paradise for swindlers, spoofers and peddlers of nutty conspiracy theories. In a world of instant information even large media organizations lack the time and resources to do proper research and ordinary people, bombarded on a daily basis by sensational events and stories, lack the mental bandwidth for scepticism.

Technology changes fast. Human nature changes gradually, if at all. The most successful hoaxes work by filling powerful psychological needs – for tales of wonder, heroic endeavour or dark villainy remote from our everyday lives. In a sense, the hoaxer and the hoaxed are co-conspirators.

Still as Bob Marley said “you can fool some of the people all the time, but you can’t fool all the people all the time.” Or was that Abraham Lincoln? And wasn’t it Lincoln who stated so wisely “there are few errors more serious than believing everything you read on the internet?”