Published in the Nikkei Asian Review 1/4/2015

Britain was the first to break ranks. With its surprise decision to become a founding shareholder of the China- conceived Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, it earned itself a pointed reprimand from the US and touched off a chain reaction amongst other Western countries, with France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland suddenly lining up to join.

The British thinking is plain: if we don’t do it, someone else will, probably the French or the Germans. Finance remains a crucial strategic industry for Britain and the City of London is determined to maintain its status as the leading Western centre for offshore renminbi trading.

The 1960s revival of the City owed a great deal to the offshore market in US dollar bonds that developed there as a result of ill-considered tax changes in the US. The British do not want to make the same mistake as the Americans and inadvertently boost rival financial centres. Hence the drive to court China’s burgeoning financial might.

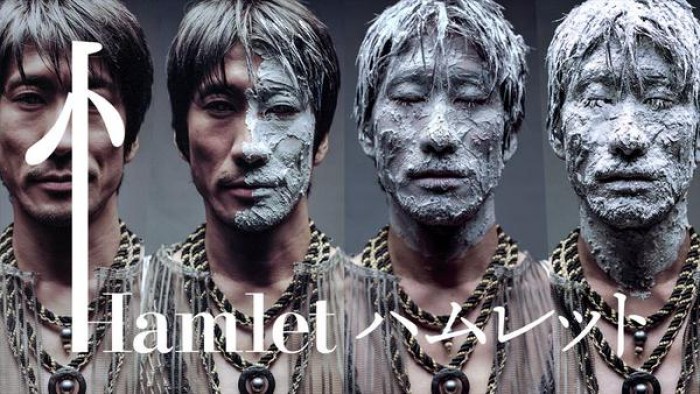

In the wake of the British decision, Australia, South Korea and even Taiwan have clambered aboard the bandwagon. Japan now finds itself in a deeply uncomfortable position, as revealed by the recent Hamlet-like equivocation of officialdom。

First Finance Minister Taro Aso’s stated openness to participation was contradicted by Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga. Then more recently the Japanese Ambassador to Beijing suggested Japan would join by June, only to be “corrected” the very next day – by none other than Mr. Aso himself!

The problem is binary. If Tokyo shuns the AIIB, it will be the only major Asian player left out in the cold. If it signs up, it will be validating a project designed to enhance China’s financial and political muscle and sideline the Asian Development Bank, which has long been a Japanese fiefdom. As Hamlet might have put it, to join or not to join, that is the question.

The decision will be a harbinger of how Japan handles the much greater geopolitical dilemma – whether to accept Chinese regional hegemony or to counter-balance it by taking on the role of deputy to the US sheriff, a job that is often unpleasant and always thankless. It is hardly an attractive choice but there may be no alternative on offer.

Britain, for the time being at least, appears to have handed back its deputy’s badge. The anonymous American official who criticized the British government’s “constant accommodation of China” had a point. Unlike the US, Japan and Australia, Britain has allowed Chinese telecoms giant Huawei to supply key parts of the telecommunications infrastructure, despite warnings by the parliamentary intelligence and security committee of “serious security implications.”

Amazingly last June Prime Minister David Cameron signed an agreement allowing Chinese companies to own and operate Chinese-designed nuclear power plants in the UK. In the current political climate, the Dalai Lama and the Hong Kong democracy movement can expect little more than the cold shoulder.

It is unclear whether China is destined to become a ”status quo” power, basically supportive of the rules of the current global system, or a disruptive force eager to subvert them. For Britain, located at the other end of the Eurasian landmass, that is an abstract question when set against pressing everyday issues of jobs and growth. For Japan, China’s near neighbour and recent colonizer, it’s a matter of overwhelming importance.

Setting up an investment bank is a different matter from making military threats and territorial claims, but the will to challenge the US-dominated global financial architecture is overt. A Shanghai-based “BRICS” version of the IMF is already in the works and the Silk Road Investment Fund has been grandly talked up as a Chinese Marshall Plan.

As the renminbi internationalizes – with the help of the City of London – it will have a growing role as a reserve currency and the global presence of Chinese banks will expand accordingly. A flood of cheap remninbi loans to the Asian region would be an effective means of exercising economic control and the political influence that comes with it. Japan’s presence could be drowned out by the sheer scale of the financial flows.

Is there nothing Japan can do to ward off this potential financial blitzkrieg? One possible counter would be to revive the idea of turning Tokyo into an international financial centre, which ran aground in the mid-noughties because of the absence of high-level backing. In Japan finance has never been considered a key sector in its own right. Whereas financial intermediaries in America and Europe are accused of extracting excessive profits, the largest Japanese financial intermediaries are barely profitable at all.

To make finance a strategic priority would require a huge change in thinking in Japan, spanning the regulatory culture and taxation. Whereas Britain lures high-flying foreigners through a generous tax regime for “non-doms” (non-domiciled foreign residents), Japan is introducing swingeing new taxes that will deter wealthy foreigners from becoming residents. Nonetheless creative use of the “special economic zones” that Prime Minister Abe has proposed could provide the right environment.

Japan also needs to make a special effort to ensure the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) happens – not so much for the alleged economic benefits as for the political advantage of being a core member of a large and wealthy economic bloc that does not include China.

According to Lord Palmerston, a famous British statesman of the mid-19th century, “nations have no permanent friends or allies, they only have permanent interests.” The prosperity of the City is a vital British interest — with a much longer history than friendly relations with the US, Japan or China – so joining the AIIB is true to historical form. Japan’s response will be a clear marker of how it sees its own vital interests. And the decision cannot be avoided. Even Hamlet made his mind up in the end.