Published in the Nikkei Asian Review 13/11/2014

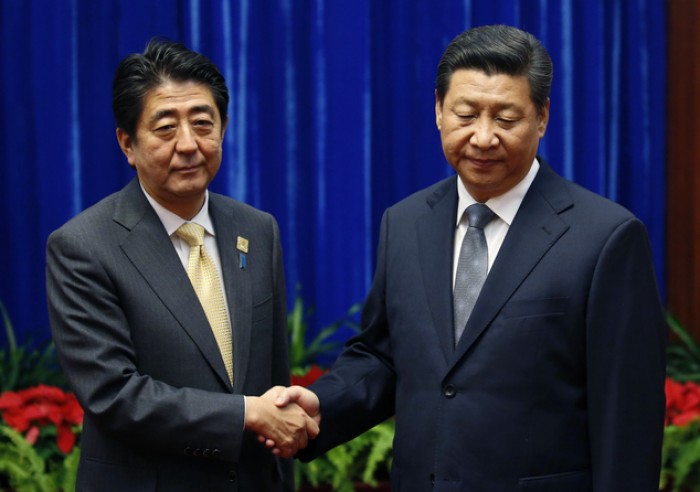

Chinese President Xi Jinping looked as if he’d dined on some bad sushi the night before. Japanese Premier Shinzo Abe looked as if he’d eaten a Chinese dumpling long past its expiry date. Such were the expressions on their faces as they went through the stage-managed ritual of a photo op at the recent APEC conference in Beijing.

The unnatural body language spoke volumes, yet the key point was that the deed was done. Through the universal symbolism of a handshake, the leaders of the world’s second and third largest economies recognized that a de-escalation of tensions was in their mutual interest. In a nostalgic throwback to the Cold War era, agreement was reached to establish a “hot line” between the two countries, intended to help prevent a random incident blowing up into a military clash.

It is sometimes suggested that Mr. Abe and Mr. Xi are nationalists who bear personal responsibility for the dramatic worsening of relations between their countries. On this interpretation, if, for example, Mr. Abe were to cease visits to Yasukuni Shrine and Mr. Xi were to wind down the “patriotic” anti-Japanese propaganda, the tensions would dissipate and good neighbourliness would reign. Unfortunately the evidence points the other way. Instead of Mr. Abe and Mr. Xi creating the problems, it was the problems that created Mr. Abe and Mr. Xi, or at least dictated their paths.

Remember that the very nadir of Sino-Japanese relations occurred in August 2012, when mobs rampaged through Chinese cities trashing Japanese factories and stores in reaction to the Japanese government’s purchase of the Senkaku Islands (known as the Diaoyu Islands in China) from a private individual. At the time Mr. Xi was still awaiting nomination as China’s paramount leader and Mr. Abe was not even the leader of his own party, let alone prime minister.

Japan’s leader then was Yoshihiko Noda of the middle-of-the-road Democratic Party of Japan. The DPJ had won power in 2009 on a platform which included reducing reliance on the US and cultivating friendly relations with China and other Asian countries. It didn’t work out.

Recently the respected investor Jim Chanos called Mr. Abe “the most dangerous figure in Asia.” Countless articles have suggested that nationalism is literally in the Abe DNA thanks to his maternal grandfather Nobusuke Kishi, a former prime minister who was once held, but never indicted, as a war criminal. Rarely mentioned are his pacifist paternal grandfather and moderate conservative father. Mr. Abe is indeed on the right of his party but he is also a pragmatist. A cultural conservative, he has found himself championing such atypical causes as “womenomics”, higher wage settlements, stronger corporate governance and the internationalization of Japanese universities. More to the point, in his earlier brief spell at the helm, in 2007, Mr. Abe mended ties with China that had frayed under his predecessor, Junichiro Koizumi, who visited Yasukuni no less than six times.

What has changed since then is that China has become a great deal more powerful and assertive. The Chinese Dream, as interpreted by the Communist Party, includes the reversal of China’s century of humiliation and the restoration of its status as a great power. Also for the first time in its history, China is now massively reliant on energy and other resources brought in from far-off foreign lands. The development of the capability to protect this supply chain, by force if necessary, is inevitable, as is the urge to dominate the rest of the region.

Japan has its own national dream, going back to the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which is to be a leading player in the region and the world and protect its independence and distinctive cultural attributes from a position of strength. The clash of interests is real and will likely outlast the tenures of Mr. Abe and Mr. Xi. It’s a version of the Chinese phrase “same bed, different dreams” – “same region, dichotomous dreams.”

The good news is that both men are realists with a clear appreciation of the risks and a personal authority that derives from a powerful policy agenda – Abenomics in Mr. Abe’s case and the anti-corruption drive for Mr. Xi. There appears to have been a tacit understanding that economic issues should be separated from political issues. Despite the heated media rhetoric, often aimed at Mr. Abe personally, China has not repeated the consumer boycotts of 2012 or the embargo of strategic exports of 2010. Japanese FDI into China has indeed fallen sharply – partly because of political risk, but also because Chinese wage costs have risen so much. Meanwhile the number of Chinese tourists coming to Japan has risen 80% in the last year and is now three times the number of American tourists. They make substantial contributions to the profits of high-end stores in the Ginza, electronic retailers in Akihabara and even the Yoshiwara, Tokyo’s ancient and much-storied red-light district.

The great question is whether the flow of people, products and money will eventually overwhelm the geopolitical issues. Probably not, but with luck it will keep the rivalry manageable and, who knows, may encourage the two leaders to offer a half-hearted smile next time they pose for the cameras.