Published in the Mekong Review February 2019

“He was beyond all bounds of normality,” says one of the key Nissan conspirators. ”So we had to be even more abnormal than him.”

Not for nothing was their target known as the “Emperor” of Nissan Motors, Japan’s second largest auto producer behind Toyota. A big figure with powerful political connections, he had done great things for the company in the past.

More recently, though, his arrogance and sense of entitlement had swollen to extraordinary proportions. His contemptuous treatment of subordinates and suppliers was ugly to behold, his monthly expenses equivalent to a middle manager’s annual salary.

Opposing the Emperor publicly was not a good idea: promising careers had been destroyed by a single critical phrase. The only way forward was to bypass the usual corporate apparatus of committees and meetings. Instead the conspirators would do their own detective work, amassing the incriminating evidence in painstaking detail.

Needless to say, the whole operation would have to be shrouded in total secrecy. Then, when the timing was right, the story would burst on the world like a bombshell.

And that was exactly what happened. In early 1984, Focus – a Japanese photo-magazine that covered political and show-biz scandals, as well as gruesome accidents and sexual shenanigans – published photographs of a tubby middle-aged man on a 40 foot yacht in the Sajima Marina, not far from Yokohama. With him was a lissom beauty several decades his junior.

The tubby man was Ichiro Shioji, head of the Nissan company union, which boasted 230,000 members, and also chairman of the Federation of Japanese Auto Workers’ Unions.

A Nissan man since 1953, Shioji had risen to a position of exceptional power, effectively running the company in conjunction with the equally long-serving CEO, Katsuji Kawamata. He hobnobbed with top US union officials, such as Walter Reuther, and gave interviews to the New York Times.

Shioji owned the yacht, though it was unclear how he had been able to afford it on his relatively modest salary – or his seven bedroom house, pricey golf club memberships and other extravagances.

His guest on the yacht was one of at least nine women he was involved with, including another pianist who he brought back from Los Angeles on one of his frequent trips and installed in a Tokyo apartment. The eight-man crew of the yacht were all Nissan employees “volunteering” their time.

Needless to say, it was not a good look for a union official who was supposed to be devoting his energies to securing a fair deal for his hard-pressed members. Bluster as he might, the “union aristocrat”, as he came to be known, could not refute the allegations of bullying, sexual harassment and misuse of company resources.

All this we know thanks to Top Secret Files of Nissan Motor, a blow-by-blow account authored by Noriaki Kawakatsu, one of the seven anti-Shioji rebels, and published expeditiously in December 2018, just as another Nissan scandal, involving Carlos Ghosn, was making worldwide headlines.

In 1984, Kawakatsu was a humble section-chief in the company’s PR department, but he and his band of brothers were convinced that there could be “no future for Nissan” with Shioji in power.

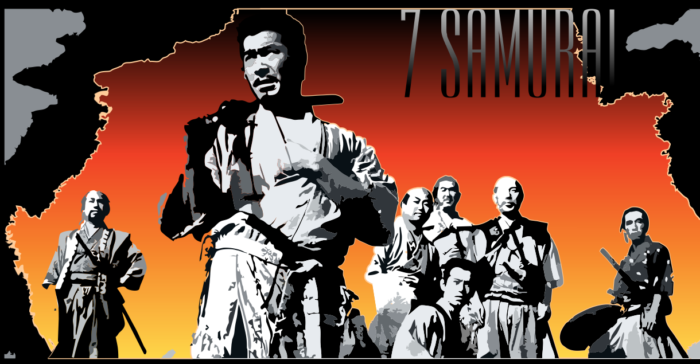

Like the low-level samurai who were the engine of the Meiji Restoration one hundred and fifty years ago, they risked everything to smash the dysfunctional status quo. Kawakatsu himself staked out the marina, sometimes accompanied by his wife and baby, and spent months trawling through Ginza nightclubs in an effort to identify the mystery woman on the yacht.

As with the Carlos Ghosn affair today, there were substantive issues at stake as well as dictatorial behaviour and financial excesses. Under the Ghosn regime, Nissan loyalists were reportedly chafing at the prospect of a full merger with Renault, already a dominant force thanks to its 43.5% shareholding. In the early 1980s, Shioji was dead set against the plan for Nissan to build an auto production hub in the UK. He even threatened strike action in domestic plants if the UK project went ahead.

Shioji was on the wrong side of history. By this time, his supporter and friend Kawamata had stepped down from the CEO role and Takashi Ishihara, a tough ex-rugby player who had been at Nissan for 48 years, had taken over the helm. The U.K. plant had been approved at the highest political level in both countries. It was to be the first stage in a vital strategic move, the internationalization of Japanese auto manufacturing.

Today Nissan’s Sunderland plant is the largest auto factory in UK history and has produced 9 million cars since opening in 1986. Nissan’s plant in Smyrna, Tennessee is even bigger. Both are non-unionized. The idea of a major player in the global auto market manufacturing only in its home country would be absurd.

Like Ghosn, Shioji made an invaluable contribution in the early years of his career, having the guts and drive to solve problems that nobody else could handle. In the early 1950s, communist-led unions were crippling the company with strikes, often featuring mass demonstrations and violent clashes. Shioji, who relished confrontation, organized the moderates and rapidly advanced up the union hierarchy, using every trick in the book to crush the radicals.

Prince Motor, a smaller company which Nissan swallowed up in 1966, also had a militant labour union which had to be tamed by fair means or foul. Again, Shioji delivered.

Even after the era of union militancy was over, harmonious relations between organized labour and management were an overriding priority in Kawamata’s eyes. Shioji was the ever reliable go-to guy when problems arose. Hence the tolerance for his Godzilla-sized ego and interference in personnel and strategic decisions.

The other side of the coin was that Nissan remained far behind dynamic rivals like Toyota and Honda in productivity and lacked their reputation for quality and innovation. Whereas Toyota prospered under the watchful gaze of the founding family and Honda was still influenced by its inspirational founders, Kawamata had been despatched to the board of Nissan by the Industrial Bank of Japan (now part of the Mizuho financial group).

With a banker at the top, inertia reigned. Governance did not extend beyond making sure loans were duly serviced. Profitability was poor, the balance sheet loaded with debt. With the exception of its 1970s muscle car, the Fairlady Z, Nissan’s product line-up was deadly dull.

Kawakatsu and the other salarymen samurai did succeed in dethroning Emperor Shioj, who gave up his all his corporate posts by 1986 and passed away in 2013. During Japan’s late 1980s boom, all appeared to be going well for Nissan, as it did for corporate Japan as a whole. But as a wise man once said, it is only when the tide goes out that you can tell who is wearing swimming trunks.

In the 1990s, Japan’s economic tide went out much faster and further than anyone could have imagined. What was revealed at Nissan was not pretty. The company was hovering on the brink of bankruptcy and its banker backers were too weighed down with dud real estate loans to help.

That was when the French auto company Renault rode to the rescue. Putting Nissan back on its feet after decades of poor governance and weak management would be a tall order, but luckily Renault had just the man for the job, a brilliant young executive known for his ruthless cost-cutting. His name was Carlos Ghosn.

If institutions learn from their mistakes, then Nissan and other Japanese companies will soon develop much stronger governance systems that will include more outsiders and prioritize transparency and accountability. Whistle-blowers and scandal-mongering media have an important role to play too, in monitoring politics as well as business.

For there is no other answer to Lord Acton’s time-tested adage that “power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”