Published in the Nikkei Asian Review 27/10/2014

“If this guy prints more money between now and the election, I dunno what y’all would do to him here in Iowa, but we’d treat him pretty ugly down in Texas.”

Such were the words of Texas Governor and Republican presidential hopeful Rick Perry in August 2011. The “guy” in question was Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, whose policy of quantitative easing (QE) Perry went on to describe as “almost treasonous.” If the Texan’s words seemed to come from an old-school Western, so did the response of Bernanke. Evidently aware that “a man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do”, he journeyed to El Paso in deepest Texas and explained the purpose of monetary policy to soldiers at Fort Bliss.

In most developed countries, central banks are independent entities. Insulated from the hurly-burly of politics, they are supposed to formulate the best possible policies in a cool-headed, technocratic manner. Such is the theory anyway. In reality monetary policy has always been highly political and has become increasingly so in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Economic conditions are more complex and confusing than ever. Central bankers need intellectual flexibility, a close understanding of the balance of economic risks and, not least, the Bernanke-style courage to face down opponents, just as Gary Cooper’s sheriff took on the gunslingers in Fred Zinnemann’s 1952 film, High Noon.

Haruhiko Kuroda, Governor of the Bank of Japan, now finds himself in a position not dissimilar to Ben Bernanke’s in 2011. The initial burst of unconventional monetary policy clearly achieved results – inflationary expectations are higher, asset markets have surged and corporate profits are booming. Even so the reflationary process is at an early stage and there is little “feel good factor“ at street level. No surprise, then, that the patch of economic weakness of the past six months has emboldened the critics of Abenomics and Mr. Kuroda’s monetary policy in particular.

Former Finance Minister Fujii recently claimed that quantitative easing was a mistake and called for intervention in the currency market. A group of senior LDP members, including ex-Minister of Administrative Reform Seiichiro Murakami, called on Mr. Kuroda to cease easing as soon as possible. A prominent business association in the Kansai region complained about the weak yen directly to Mr. Kuroda.

Other critics of Abenomics were comfortable under deflation and would be happy to see it return. Some represent interest groups that do indeed suffer from currency weakness but kept quiet while benefitting from the strong yen of previous years. More general is the search for a plausible narrative to explain away the poor performance of the Japanese economy in recent months. The yen is a useful scapegoat, even though in traded-weighted terms it is hardly changed since the start of the year.

The real reason for the economy’s loss of momentum is not hard to identify. It is the decision to hike the value added tax by 3% in April, which had the predictable effect of stalling consumption. The financial bureaucracy, the major opposition parties, the business community and the media were all complicit in this policy blunder and are loathe to admit it. Worse, pressure is mounting on Prime Minister Abe to green-light a second tax hike for next year. One hopes this time he’ll have the gumption to withstand it.

In terms of monetary policy the key point is that you can’t aim at two targets at the same time. If M. Kuroda were to attempt to stabilize the yen, it would mean abandoning the 2% inflation goal that is at the heart of Abenomics. Both he and Mr. Abe should make it clear that this is out of the question. Furthermore, in a deflationary global environment a weak currency is a useful weapon. It benefits not just exporters, but domestic industries that compete with imports, raises the yen value of Japan’s bulging portfolio of overseas assets and encourages companies to favour on-share production – as exemplified by parts maker Denso’s recent decision to add new capacity at home.

Mr. Kuroda’s other enemy is complacency. The BoJ’s internal research places too much emphasis on output gap analysis, which has been abandoned by the Fed and the Bank of England, and opinion surveys that have no track record of accuracy. The reality is that achieving the inflation target is a multi-year process that will probably require several rounds of QE. The next round is required soon, as the recent decline in the oil price means that Japanese CPI will likely be closer to 0% than 2% by next summer.

After his confrontation with Rick Perry, Bernanke went on to introduce a third round of QE. He then announced the tapering strategy which would bring the Fed’s asset purchases to a gradual close and rode off into the sunset like the wounded hero in Shane, George Steven’s classic 1953 Western..

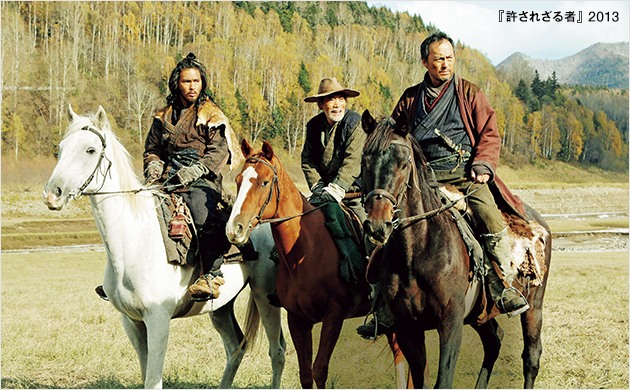

Japan understands Westerns too, as the recent Japanese remake of Clint Eastwood’s The Unforgiven demonstrates. If Mr. Kuroda can despatch the hostile forces as coolly as Ken Watanabe does in the final showdown, reflation will soon be back on track.