Published in the Nikkei Asian Review on 31/3/2016

Finally the dilly-dallying is over. The purchase of Sharp by Taiwan’s Hon Hai Precision Industry, also known as Foxconn, has been approved by both parties.

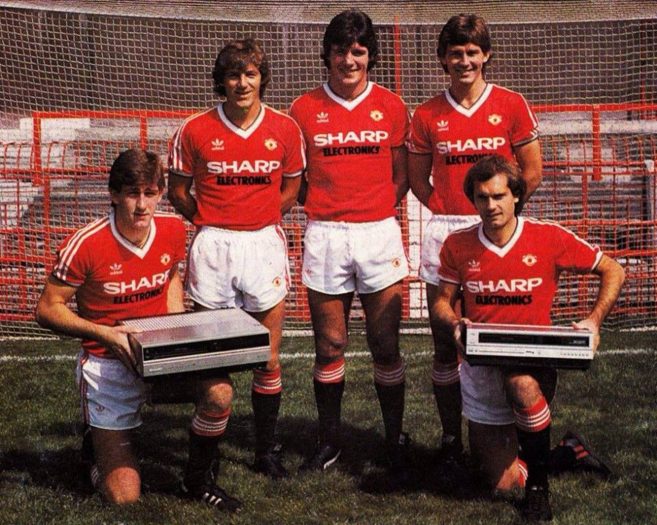

The deal marks the end of the Japanese company’s 104 year history as an independent entity. Originally a manufacturer of mechanical pencils, Sharp became a pioneer in radio and TV manufacture and produced the world’s first pocket calculator. It was one of several Japanese groups – others being Sony, Panasonic, Toshiba and Hitachi – that bestrode the global electronics market like giants in the 1970s and 1980s, but have subsequently seen their fortunes dwindle.

In contrast, the rise of Foxconn, founded by Chairman and CEO Terry Gou in 1974, is principally a twenty first century story. Today the company is the world’s largest contract manufacturer, with revenues of 130 billion dollars and a stock market capitalization more than 15X greater than Sharp’s.

This it has accomplished on the back of two powerful mega-trends – the emergence of China as the world’s low cost manufacturing hub and the ascendancy of Apple, with its “platform company” model of outsourcing production. Most of Foxconn’s production is in mainland China, where it operates a chain of huge “factory-cities” that employs over a million workers. Its biggest customer by far is Apple.

These twin phenomena will not continue forever – in fact, may have peaked already – but together they put a merciless squeeze on the Japanese electronics industry. On one side many consumer and industrial electronic products were “commodified,” as prices fell in synch with the cost of production. On the other side, Apple’s innovations, design skill and brand power allowed it to dominate the higher end of the market while generating extraordinary margins.

Japanese companies responded to the challenge in different ways; through off-shoring, withdrawing from unprofitable businesses and becoming suppliers of key components to the I-phone and I-pad. Most were too cautious. Sharp was too bold – effectively betting the farm on two new product lines, solar panels and LCD displays for flat-screen TVs and computers.

These were considered high potential by just about everybody at the time, but they required vast capital expenditures and ended up being “commodified” at alarming speed. Sharp found itself in an impossible position in which, as the Japanese proverb says, it was “hell to go forward and hell to go back.”

It is tempting to see the Foxconn takeover as a symbol of Japanese economic malaise; tempting, but wrong. Creative destruction is the hallmark of a dynamic economy and if anything Sharp’s bankers had allowed it to stagger on too long. The other potential acquirer, the state-backed Innovation Network Corporation of Japan, would have been unlikely to make the tough decisions needed to sort out the valuable parts of the company’s operations.

GOU VS GHOSN

Terry Gou’s plan offered a better deal to shareholders too. With improved corporate governance being a key part of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s reform program, it would have been a backward step to reject the higher bid on vague grounds of protecting the national interest. Especially in the electronics industry, openness is realism. Supply chains are global and the relations between key players are constantly shifting.

Foreign takeovers of Japanese high-tech companies have been as rare as midwinter cherry blossom, but it is noticeable that the only other significant example, Applied Materials’ acquisition of Tokyo Electron in 2013, also took place under the Abe premiership – though was scrapped 18 months later, due to US anti-trust concerns.

The model for a successful foreign takeover is Renault’s 1999 acquisition of Nissan, then on the verge of bankruptcy. Carlos Ghosn was drafted in as CEO and implemented a rigorous rationalization programme that slashed capacity and drastically shrank the number of suppliers. Today Nissan is one of the world’s most successful auto companies and Ghosn, now CEO of Renault too, is a widely admired figure both in Japan and France.

It is emblematic of today’s world that this time the acquirer is a first-generation Asian entrepreneur rather than the boss of a time-honoured European or American firm. Still Terry Gou will have his work cut out to pull off a Ghosn-style turnaround. The problem with Nissan was its balance sheet, not the competitiveness of its cars, and it was operating in an industry where change was accretive rather than disruptive. On both scores Sharp is much less favourably placed.

Even so, the deal is a positive step for Japan. If it hits difficulties, as many takeovers do, it will still have been a positive step. Foreign direct investment – whether in the form of mergers and acquisitions or building from scratch – is important not so much for the capital it brings, but for the new ideas, techniques and ways of doing business it introduces.

IN BUSINESS SINCE 718 A.D.

What Japan’s consumer electronics companies have lacked is not creativity – Sharp launched its Zaurus personal digital assistant as long ago as 1993 and the world’s first camera-phone in 2001 – but commercial savvy and strategic vision. Sharp chose to stay domestic when all the action was global; it did not protect its intellectual property sufficiently; it failed to make the right alliances; it did not prioritize and still makes far too many diverse products.

The most important things that Terry Gou can bring to Sharp are deal-making skills and understanding of the global big picture. What he is getting in return is the opportunity to break away from dependence on China and Apple. Without innovative products of its own Foxconn will never be more than a supersized job-shop operating on wafer-thin margins.

It could work. After all Apple itself was on the verge of bankruptcy in 1997. If it does, it could inspire other Japanese electronics majors to make deals with foreign companies rather than gradually sinking beneath the waves.

Japan knows a lot about corporate longevity. The Sumitomo group was founded a century before the United States. Sude Honke, Japan’s oldest sake brewer, has being going since 1141 and Hoshi Ryokan, a hot springs hotel, since 718. Such businesses have survived for so long because they have provided what customers wanted through centuries of upheaval.

In comparison Sharp is a mere spring chicken. If it follows the same principle, some parts of its business will live on and prosper, albeit in a different guise.