Published in the Nikkei Asian Review 10/12/2019

In Japan it seems these days that it is the conservatives that want to change things and the progressives that want to cling to the status quo. An apparently minor, but potentially highly significant example is the Abe government’s proposal to change the order of Japanese names when written in the Western alphabet.

From the early years of the Meiji period (1868-1912), Japanese people have identified themselves to foreigners in the common Western style of given name first followed by family name, as in this article. In native Japanese, however, the order is always the other way round – family name followed by given name.

As of January 1st 2020 that will officially change. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe will become known as Prime Minister ABE Shinzo (capitalization of the family name is also recommended) and others in public sector roles will be expected to do the same.

There is no obligation on ordinary citizens to follow suit, but the advantages of standardization suggest that over time the new format is likely to win out. In which case, for example, actor Ken Watanabe would become WATANABE Ken and Softbank Group’s Masayoshi Son would become SON Masayoshi.

To Westerners the upheaval may seem unnecessary and confusing, but from the Japanese perspective it represents authenticity and normalization. No longer doing things just to convenience Westerners is part of the point.

The initiative originates in the early years of this century when the Cultural Affairs Agency issued an advisory on use of the native name order in English contexts. Lacking heavyweight political backing, it was totally ignored. This time, rising stars of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, such as Defence Minister Taro Kono, have been vocal in support. It seems the public is on side too. A recent opinion poll showed 60% in favour of the change.

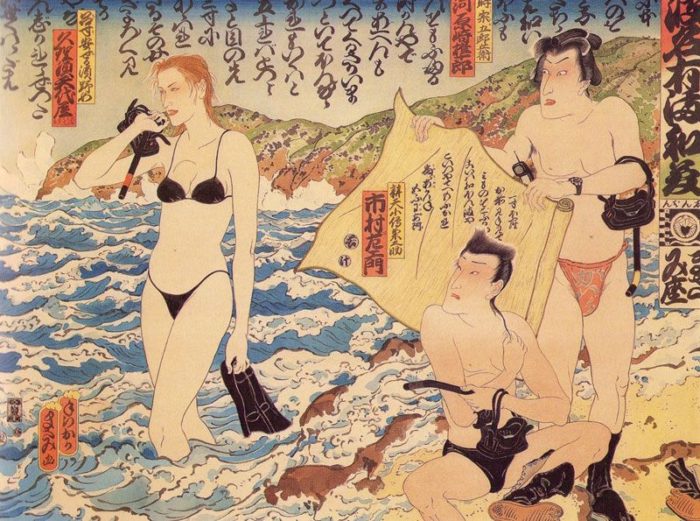

The justification, as set out on the CAA’s website, is that Japan is merely aligning itself with other East Asian nations such as China, Vietnam and South Korea, all of which put the family name first. And as a practical matter, the foreigners that a Japanese person is most likely to meet these days are from the old Sinosphere. There are four times as many Vietnamese now resident in Japan than North Americans. Of the 31 million visitors to Japan in 2018, 73% came from East Asia. The days when the typical foreigner in Japan was a tall Caucasian with a big nose are long gone.

Which brings up a much larger point. East Asians put their family name first because family affiliation was traditionally the most important information about a person, the individual identity coming second. Not even Mao Zedong, who oversaw the destruction of so much of traditional Chinese culture, sought to be called Zedong Mao by foreigners.

In essence, the East Asian format signals a more communitarian society, the Western format a more individualistic one. Japan’s use of both simultaneously – on either side of the same name card – is a characteristic strategy deriving from specific historical circumstances.

One hundred and fifty years ago, Japan was engaged in a programme of headlong modernization neatly encapsulated by the phrase “Datsu-A, Nyu-O,” meaning “Leave Asia, Join Europe”. That slogan was associated with the famed educator and writer, Yukichi Fukuzawa, who saw rapid Westernization, cultural as well as technological, as the only way for Japan to survive.

In an age when Westerners ranked ethnic groups in terms of “cultural advancement,” i.e. similarity to themselves, use of the given-name-first format was a tiny but crucial element in the national endeavour to convince Westerners that the Japanese were peers and equals, rather than “backward” people ripe for invasion and colonization.

So is Japan’s newfound desire to align itself with its neighbours a harbinger of a “Datsu-O, Nyu-A” (“Leave Europe, Enter Asia”) process? Perhaps so. In today’s world, East Asia connotes high-tech manufacturing and rapid growth, not the poverty and weakness of Fukuzawa’s era. Furthermore, global norms themselves are becoming more varied and multi-cultural, and conforming to an exclusively Western template is starting to look dated.

But there is more to it than mere pragmatism. In her brilliant and provocative book, The Fall of Language in the Age of English, novelist Minae Mizumura describes the extraordinary inferiority complex Japanese intellectuals have felt towards their own language and – by extension, though she doesn’t say so directly – their culture.

Arinori Mori, appointed Japan’s first education minister in 1885, wanted Japanese to be replaced by English as the national language. Yoichi Funabashi, Japan’s most celebrated newspaper columnist, made a similar case in a book published in 2000. Even Ikki Kita, the ultranationalist thinker executed for inspiring the failed coup d’état of 1936, believed that his own tongue was “exceedingly inferior” and should be replaced by the artificial language of Esperanto.

There were also periodic campaigns to have Japanese written in the Western alphabet, notably by the United States Education Mission to Japan in 1946. Western theorists of the time considered ideograms like Chinese kanji to be primitive and undemocratic, compared to the phonetic scripts of the West.

Language is political, as Mizumura demonstrates. By projecting their domestic identities to a global audience for the first time, the Japanese are engaging in a symbolic act of self-assertion and seeking to put such complexes behind them.

It could be considered a dry run for a much more contentious act of assertion and normalization which will soon be on the menu – amendment of the Japanese Constitution.